By Michael McDowell Geri Marz joined Trailkeepers about a year ago. She’s volunteered weekly almost ever since joining, and put in many volunteer days over the past winter, spring, and summer on a trail crew building the new…

By Cheryl Hill and John Sparks

A group of men camped at Bagby Hot Springs in the 1920s.

The Bagby Hot Springs Trail #544 is one of a number of trails that once led to the 136-degree pools above the Hot Springs Fork of the Collawash River. American Indians had long known about and used the hot springs along the Hot Springs Fork when prospector Robert Bagby visited the site in 1881 following a rough sign with an arrow labeled “Hell.”

The current Bagby Hot Springs Trail, originally the route taken by visitors coming up from the valley of the North Santiam and called the South Fork Mountain Trail, now is a truncated stretch of 12 ½ miles, running from Elk Lake in the south to the Hot Springs Trailhead on Forest Road 70. It bypasses the prominence of Battle Ax and bisects the Bull of the Woods Wilderness. Except for the section from FR 70 to the hot springs, the trail can be very brushy although always obvious. It’s best to wear long pants and add rain pants when the foliage is wet. If you really want to do a good turn, bring pruners and lop away at a few of those bushes!

According to the Forest Service, another trail coming from the west was called the Molalla Trail. It continued east towards Pansy Lake, merging with the current Mother Lode Trail. One main branch of the trail followed the Molalla River; another originated at Elk Prairie, east of Scotts Mills. Prospectors tapping the seams of the Little North Santiam and Elk Lake Creek basins used the trail, and would stop at the springs to avail themselves of the properties. It was also a sheep trail, according to Tom Carter, who was a forest ranger from 1918 to 1926. This trail appears on the 1916 Oregon National Forest Map, and much of it continued to appear on maps until it disappeared with the 1966 edition of the Mt. Hood National Forest map. As was the case with many trails, this one was supplanted by a network of logging roads built during the 1960s. However, one little-used but intact stretch of the western section still exists, the High Ridge Trail in the Table Rock Wilderness, which begins at the Old Bridge Trailhead.

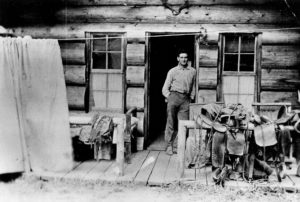

Undated photo of a man at Bagby Guard Station

As for the hot springs themselves, after Bagby’s visit the secret was out. Other visitors began arriving to partake of the waters, usually filling buckets with water from the creek to cool the hot springs water, until primitive structures were constructed in 1908. A Forest Service guard station and shed, now on the National Register of Historic Places, were built there in 1913. The station served as an operations and communications link in the fire protection system. A new guard cabin was erected in 1974. The first proper bathhouse was built around 1939, and burned down in 1979. The Friends of Bagby Hot Springs, at first opposed by the Forest Service, pursued an effort to rebuild the structures over a period of years. Now that a concessionaire monitors the site all year and a number of restrictions are in effect, some of the former issues, such as car clouting at the trailhead and boisterous drunken night parties, have considerably diminished.

Bagby communal tub in 2008.

Today’s visitors need to pay a $5 “soaking fee” which is not covered by the Northwest Forest Pass (the pass is no longer required and there is no parking fee). This fee can be paid at the trailhead kiosk or at the Ripplebrook Ranger Station on your way in. Upon paying the fee, you will receive a wristband that you need to wear while soaking. There is a campground near the trailhead, or you can backpack in and set up a tent at the primitive campground near Shower Creek Falls, just south of the hot springs area. Current regulations include a ban on nudity outside of the bathing area and a ban on alcohol. The hot springs are open as long as the access roads are clear, but every winter there are visitors who get stranded because their vehicles get stuck in the snow. If you can make it, the best times for an uncrowded experience are on weekdays in the spring or fall. Do the hike up the Hot Springs Fork towards Silver King Lake before you indulge in your soak!

Pack It Out (with a Twist)

By John Sparks

The north-south trail along the Hot Springs Fork still exists and, given the destination, the short stretch into Bagby Hot Springs is extremely popular at all seasons. However, the popularity comes at a cost—the fact that many users have no concept of Leave No Trace (LNT) ethics and leave unsightly tidbits of trash decorating the verges of the trail. With Bagby, the presence of a concessionaire and volunteers who practice regular cleanup has somewhat ameliorated this problem, but trash can be an issue on most short, popular trails in the state (think Wahclella Falls, Oswald West State Park, Sahalie and Koosah Falls, and Strawberry Lake).

So what should a responsible hiker do to help keep the trails clean? Usually we don’t catch people in the act and get to lecture them, so the next best thing is to clean up after the scofflaws. On every hike, try taking along three to five plastic bags (for example, the ones you use for fruits and vegetables at the grocery store) for the purpose. This is an easy solution for common trail “flowers” such as energy bar wrappers, potato chip bags, cigarette butts, and those Mylar balloons that have floated in from a toddler’s birthday party in another county. Plastic water bottles don’t even need a bag: just tuck them into a side pocket on your pack (keep one empty for the trash pickings).

Then there are the more unpleasant trailside offerings. You’ll be forgiven if you don’t tackle these, but at least give the issue consideration. I’m thinking of those little white dabs of toilet paper and, something that seems to be becoming increasingly common, the knotted dog poop packet. If you’re a true LNT warrior—and I have to admit the condition of some of those ornamentations has often trumped my zealotry—use a plastic bag as a mitt to gather up the offending object, tie it up, and deposit all in your principal trash bag.

Finally, if you arrive at a massive dump site beyond your capabilities, post your finding on Oregon Hikers in the Trail Rx Forum. Give as precise a location as possible and add a couple of photos. Land managers from many agencies monitor the forum and may be able to send out a cleanup crew.