By Steve Kruger, Executive Director, Trailkeepers of Oregon On October 27, trails professionals from nonprofits, outdoor recreation companies, and land management agencies came together in Bend, Oregon, for TKO’s first crack at hosting an Oregon Trails Summit. Trails…

By John Sparks

Much of the North Fork John Day River Wilderness is a resurrected landscape, especially along its watercourses, and still recovering from placer mining operations that sifted entire stream beds and blasted away hillsides from the 1860s into the 1950s.

The North Fork John Day is returning to pristine condition. Photo by John Sparks.

One portal to the wilderness is via the upper North Fork itself, and from the North Fork John Day Campground you can hike a good loop that takes in trails established by miners, their mule teams, and later their vehicles.

Gold was discovered by Henry Griffin and his prospecting team west of present-day Baker City in 1861, nine years after Oregon’s initial strike near Jacksonville in the southwest part of the state. Within three years, placer mining operations were working up and down almost every creek in the eastern Blue Mountains. Three-quarters of Oregon’s gold production has since come from the Blues. Initially supplies were brought in all the way from The Dalles, but centers such as Baker City were soon established. The trails extended up the rivers and over high passes, and miners soon learned which areas were producing the most paydirt. The North Fork was a relatively poor district compared to those in the Powder River drainage to the south and east, but many active claims were grandfathered in when the wilderness was established in 1984.

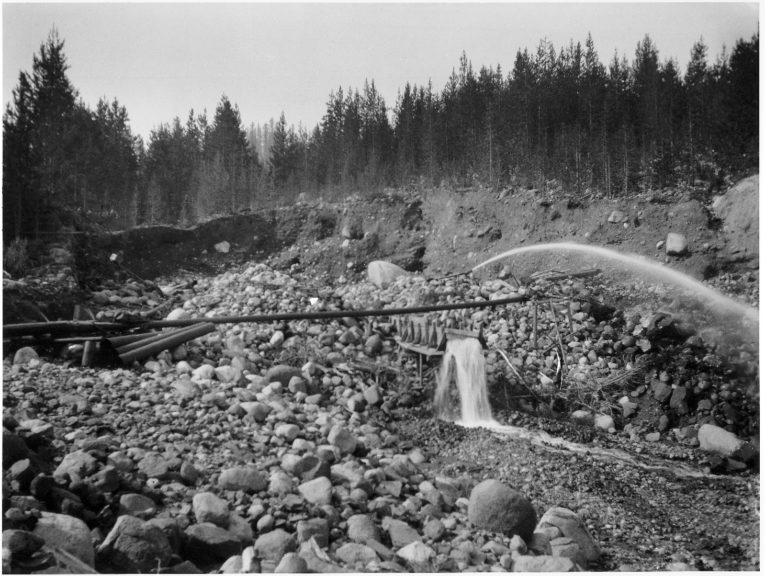

A hydraulic mining operation in the Blue Mountains. Photo courtesy of US Forest Service.

You’ll be hiking upstream from the North Fork John Day Trailhead, but even in the campground area you’ll see the long piles of larger rocks that were separated from river sediments before sluicing of the finer sediment could progress. The North Fork John Day River Trail #3022, initially a miner’s supply track, follows the river upstream for twenty-five miles, but these first few miles will reveal much about the activity in the area. Before you turn off on the Crane Creek Trail #3011 to make a loop, you’ll pass four standing miners’ cabins and the ruins of others. The claims for all of these have now expired, but Cove resident Guy Hafer worked his Blue Heaven Claim until 2004 (He died in 2007).

Claim jar on the Blue Heaven Cabin. Photo by John Sparks.

You will see Blue Heaven claim notices tacked on trees, and the claim jar with its papers is still nailed above the door of the cabin. The interior is remarkably well preserved, and Hafer’s tools are displayed on the porch. Another more famous cabin sits below the trail near the crossing of Trout Creek. This is the “Bigfoot Hilton” of Home Mines, immortalized by William L. Sullivan in Listening for Coyote, the account of his west-to-east trek across Oregon in 1985. Sullivan laid up in this log cabin for two nights during an October snowstorm. While he wrote that the cabin was clean and inviting, it has since seen some abuse and neglect. The welcome note that he found (signed by none other than Bigfoot) is no longer there.

The Bigfoot Hilton (Home Mines Cabin). Photo by John Sparks.

After Trout Creek, you begin to notice signs of more industrial mining activity, much of it associated with the Thornburg Mine. Thornburg was not a simple pan-and-sluice operation, as the huge tailing piles across the river indicate. At various points on this section of trail, you’ll come across rusting equipment and sections of eroded hillside. Larger placer operations used pressurized water cannons—the huge iron nozzles were known as “giants”—to blast ancient sediments off the hillsides, a process known as hydraulic mining. For a while, the trail actually follows the verge of a trench that conveyed water to power the cannons. Later, the Thornburg also used a Bagley dragline, a cable-operated bucket suspended from a mobile boom. The Thornburg operation began in the 1880s and continued into the 1940s, yielding from eight to twenty cents’ worth of gold for every cubic yard. During the Great Depression, the price of gold jumped from $21 to $35 per ounce, and the result was an uptick in mining activity all over gold country. By the early twentieth century, roads to supply this mine ran from the east at Crane Flats, near the ghost town of Cabell City, over the hills and down to the river, while another road, a section of which became part of the North Fork John Day River Trail, came up from Granite via Happy Prairie. Besides the riverside section of the latter road, the other road sections have gone back to wilderness.

Human activity in the area, of course, preceded the advent of the gold diggers. On December 26, 1896, the San Francisco Call reported an interesting find. Somewhere above the current trail and across the river from his mine, Elmer Thornburg found a “chamber” excavated from the hard rock containing “stone implements,” spears, arrowheads, pottery, and flints. Thornburg also reported that the “walls were nearly covered with hieroglyphics, while in the alcove rudely cut out was an image that we concluded was an idol.” Apparently, the contents of this chamber were all carefully collected and given to the Smithsonian Institution. One wonders about who preceded the fortune seekers to these ancient valleys.

If you do the loop, you’ll ford the North Fork John Day and pass through a lush campsite where visitors have fashioned an outdoor museum of sorts with odds and ends of mining equipment they have salvaged. The Crane Creek Trail, although you may not notice from the narrow width of the tread, follows a Depression-era road track that also arrives at the Thornburg Placer. This section of Crane Creek only produced a few flecks of the bright stuff, but it was enough to inspire a dredging operation in the upper reaches of the creek above Crane Flats. Dredging was the most industrial, and most destructive, method of gathering paydirt as whole creek beds were scooped up and sluiced, completely destroying the surrounding ecosystem. You can visit a partially restored dredge not far to the south at Sumpter.

However, to complete the hiking loop, you won’t visit upper Crane Creek but turn north at the Crane Creek Trailhead. The North Crane Trail #3171 heads up through forest and meadow over a rounded ridge following the narrow road track that led north from Granite (The current highway, FR 73—part of the Elkhorn Drive Scenic Byway—runs a little to the east along the valley of Onion Creek). As you near the North Fork, the trail descends through tailings of the Klopp Placer, which produced a few thousand dollars’ worth of gold per annum in the 1920s and ’30s. The slope here is a somewhat different composition than the river placers, however. Millions of years ago, a basalt flow dammed the river, resulting in a lake, which gathered sediment over a period of time, thus concentrating gold deposits. Later, a glacier, which originated at the headwaters of the North Fork to the east, worked these deposits and formed a terminal moraine. To this day, the Klopp Claim remains a private inholding almost surrounded by wilderness, but there has been no production here for decades.

True wilderness is not easy to find in the Blue Mountains. In Listening for Coyote, Bill Sullivan points out that this area of the Blues averages “six miles of road per square mile” outside the wilderness areas. On the North Fork John Day, the irony is that because the miners got there first, the slopes were never commercially logged. Now, hiking trails have co-opted old miners’ routes, and the forest and creeks are slowly healing.

Hands Off! Historical Artifacts Along the Trail

Two laws protect historical artifacts on federal and Indian lands. These are the Archeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA) and the Antiquities Act of 1906. With more clarity and “teeth” than the original Antiquities Act, ARPA carries fairly stiff penalties ($20,000 and up to one year in jail for a first-time offence) for disturbing a historical site or artifact. The latter is described as anything more than one hundred years old.

No Trespassing sign on a historic shelter. Photo by John Sparks.

The trails in mining country provide the hiker with opportunities to view the relics of a bygone age in the form of abandoned cabins, rusting equipment, earthworks, and other signs of industry and occupation. Most of what hikers will see along the North Fork John Day River Trail, however, does not currently fall under ARPA protections since there is little that remains of the nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century presence. Many of the “relics” date from the Great Depression years or later. In other parts of Oregon, this also goes for that ’49 Studebaker draped with blackberries or a rotting steam donkey carriage.

Does this give the visitor free rein to disturb, remove, or disfigure anything less than one hundred years old? Certainly, a segment of the population seems to think so, but good hiking etiquette must always be to leave objects in place. In most cases, look and take photos but do not touch or move. Explore but do not disfigure. Nudge that old cabin door open gently, and leave everything as you found it. Do not move objects closer to the trail so people can see them. Always respect signs that restrict access. In some cases, if you “discover” something off-trail that may be unknown to the general public, you may want to think twice before posting about it on the internet.

A slowly decaying Studebaker or a #9 galvanized wire that once led to a fire lookout will give delight to the next hiker who comes by, provided you let these relics rust away in peace. Naturally, however, there are some “artifacts” that should be removed. Free free to collect and treat as garbage anything left by casual visitors, such as fellow hikers, hunters, and ATV users. The forest can tolerate the driveshaft of a 1930s Moreland logging truck; a stash of empty Coors beer cans is another matter.